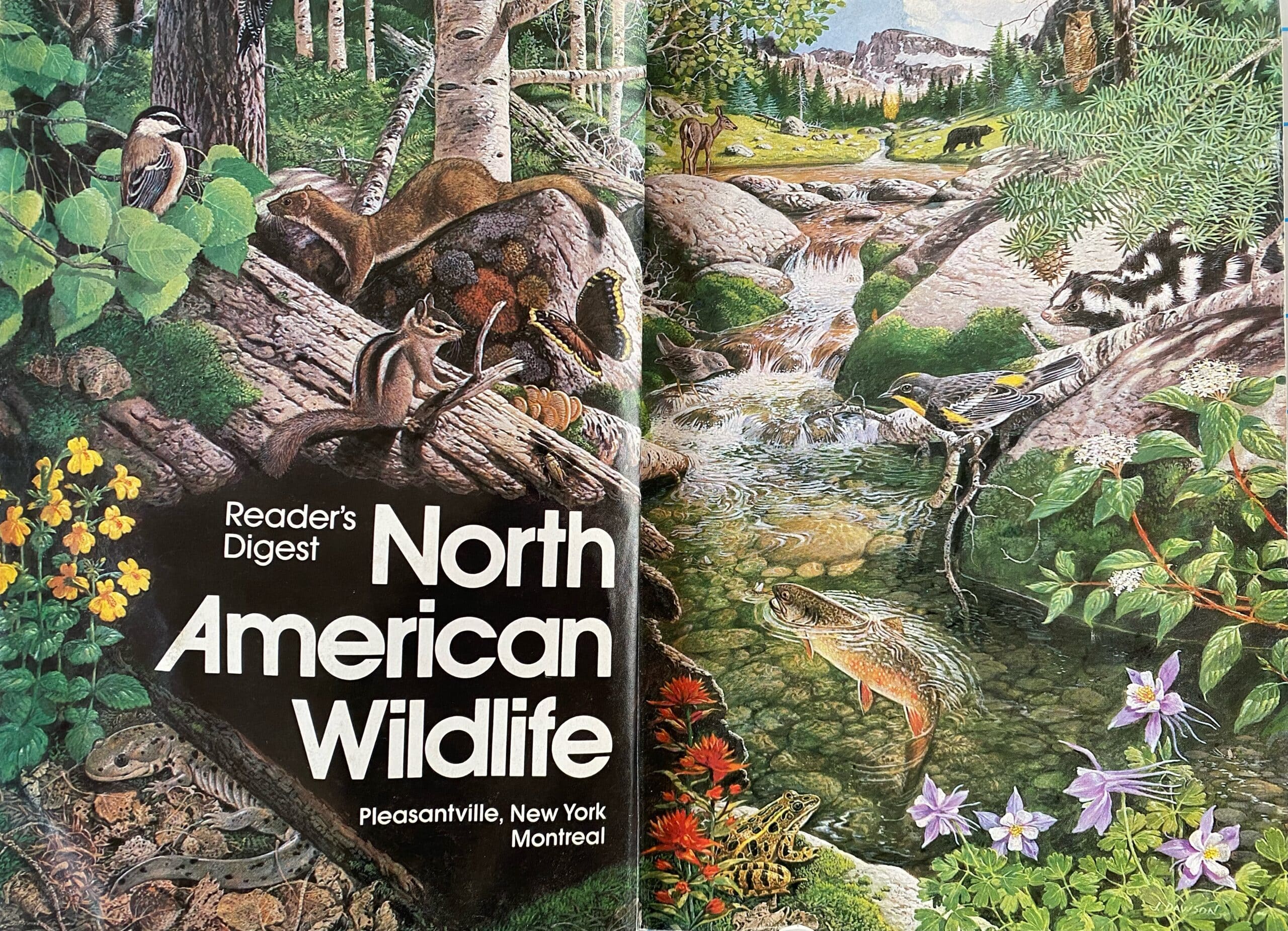

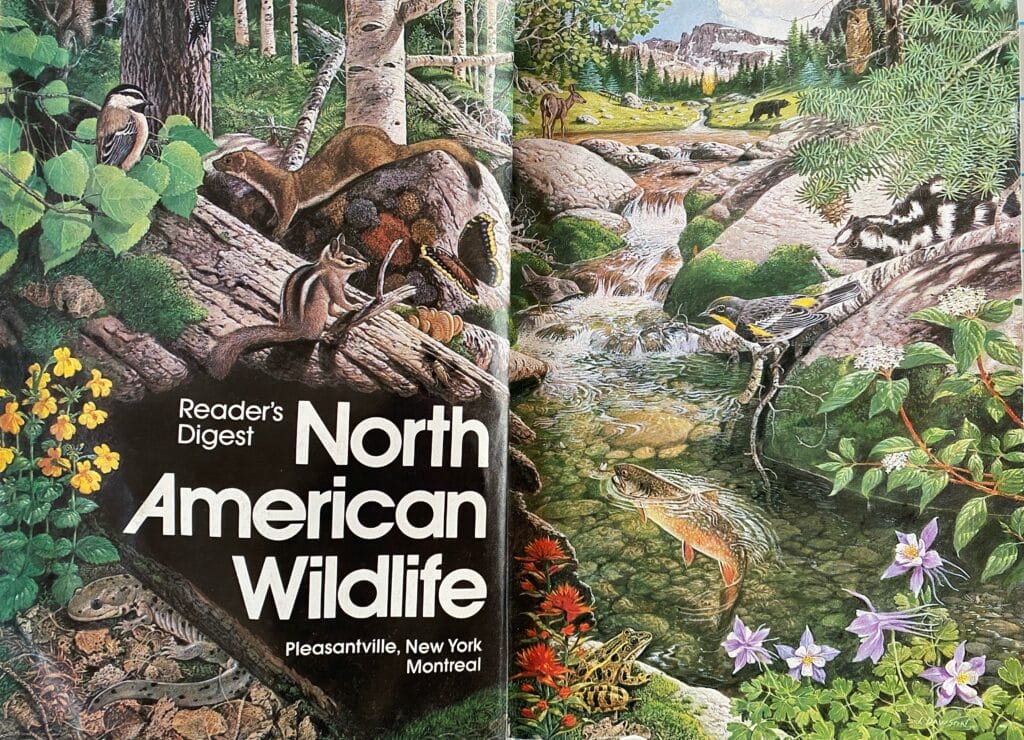

The inside front cover of Reader’s Digest Guide to North American Wildlife, published in 1982. I read this book cover to cover and was obsessed with this illustration as a child.

Adding a drawing of a pale swallowtail to another drawing of a leopard lily, using tracing paper (and tape of course).

When I have taught drawing and painting classes, one of the most revelatory things for people is that I don’t start a painting by drawing right on my good watercolor paper—not at first, anyway. I start with pencil sketches, which I typically do on tracing paper. I like tracing paper because it’s cheap and erases well; it also lets me take one bit of a drawing I like and trace it onto another drawing (for example, laying a drawing of a butterfly over a drawing of a flower). This technique allows me to work out all the elements of a layout, like proportion and arranging animals and plants in a piece. By the time I get to the good, expensive watercolor paper, I’ve settled on a composition and am ready to paint.

Learning to work this way was revelatory for me, too. I remember looking at the detailed paintings depicting nature scenes in murals and books when I was a kid, and wanting so badly to paint that way myself. I tried a couple times to paint a forest scene, but got frustrated when my simplistic sketches looked nothing like what I envisioned and my pencil marks wouldn’t erase from the heavy, textured watercolor paper. I went on to take art classes in high school and college, and then painting classes at night once I was working as a graphic designer, but it wasn’t until I was enrolled in the science illustration program that I really learned how to take my sketches and turn them into a composition.

Sketching sun cups in my backyard for a work in progress.

Before the science illustration program, I had logged in a lot of hours doing observational drawing, both in figure drawing classes and just drawing what I saw around me (buildings, people, dogs). And I’d done a lot of finished pieces, where I would do colored pencil copies of magazine photos or portraits in the style of the old masters. But I hadn’t yet discovered that I could take my sketchbook drawings and turn them into a final piece.

In the science illustration program, I learned to start combining elements. In field sketching, we drew things near and far on the same page; in botanical art, we dissected flowers and learned how to show all the parts of a plant elegantly on one page. We did assignments throughout the year with names like “Above and Below”, “Microhabitat,” and “Mystery Field ID”, all of which required us to compose a page with elements that weren’t necessarily already together in life. In other words, we might have to imagine a composition and then figure out how to put the pieces together. At long last, the kid who wanted to paint a forest scene was learning how to do it.

In my next blog post, I’ll talk about how I take those sketches and get them onto watercolor paper… stay tuned!

Initial sketch (left) and finished artwork (right) for A Day on the Mountain, written by Kevin Kurtz and illustrated by Erin E. Hunter (published by Arbordale Publishing, 2010).