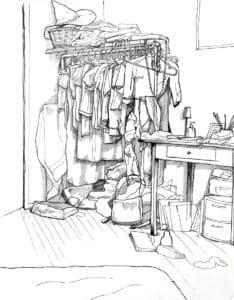

My roommate Nila’s clothes rack in our Brooklyn apartment. Pen and ink, 2004.

Like many artists, I was the sort of kid who loved to draw all the time. I was scolded more than once for daydreaming or drawing when I should have been paying attention in class. I also was interested in the natural world around me, wanting to know the names of things and always hoping to see the wild animals I read about in field guides and nature books. A class in wildlife biology in high school piqued my interest in the idea of being some kind of scientist or veterinarian, but I didn’t get very good grades in math and science, so I turned my attention toward the subjects I’d always excelled in—visual art and languages. I fell in love with typography and chose to major in graphic design, with a minor in Spanish.

I started working as a graphic designer right after college, first in California at a small firm, and then in New York as a freelancer (and also a retail clerk, babysitter, calligrapher…). But I found that the impulse to draw never went away, so while still in New York, I took night classes at the Art Students Leauge and started applying to MFA programs in illustration. My portfolio was all over the place: sketches of people in coffee shops or on benches in parks; elaborate drawings of my roommate’s clothes rack (our apartment didn’t have closets); amateurish watercolors of carnivorous plants, a subject matter that had recently piqued my interest; attempts at portraits in a Rembrandt palette and style. When I took these pieces to the schools I was applying to in New York, I was asked, “what does all this mean? Why did you choose this subject matter?” I didn’t have a good answer, because honestly, I’d been hoping that I’d learn the “why” once I was in classes. Coming from a more commercial/ graphic design background, I didn’t have an artist’s statement or the language to describe my point of view; I was used to problem-solving for clients, melting into the background in service of the projects I worked on.

A pitcher plant trap, one of the carnivorous plant illustrations from my application portfolio. Watercolor, 2004.

The first year I was rejected from every school I applied to, and the second year I was too. I remember calling my mom in tears from my Brooklyn apartment when I received the rejection letter from the last school I’d applied to. A high school English teacher, she graciously took a lunchtime call in her classroom as I sobbed. She told me that I was brave to keep trying, gave me a few words of encouragement, then reminded me that she needed to get back to her students.

I was between a rock and a hard place: I needed to go to school to become a better illustrator, but I needed to be a better illustrator before I could get into school.

Not long after this second round of rejection, I moved back to California and began to research graduate programs in illustration on the West Coast. Someone told me about the science illustration program at UC Santa Cruz, so I visited the program in person and brought my strange portfolio with me; by this time, it also included colored pencil sketches of animals and plants. I met with Ann Caudle, the then-director of the program, who paged through my portfolio, nodding as she recognized the plants I’d painted. “Sarracenia,” she mused, pausing on one of the watercolors. “Such a beautiful plant.” Hope welled up in me as I realized that I might have found the right place at last.

During that meeting with Ann, she gave me the kind of specific advice I’d been seeking. She told me to spend a little extra on 100% cotton hot press paper, rather than the student grade paper I’d be using, and suggested the kinds of work she liked to see from prospective students. She also directed me to the exhibit of that year’s science illustration student work at the local natural history museum. I remember walking into the museum, wandering through the incredible illustrations, and thinking that it felt like home.

The Sarracenia watercolor from my portfolio that I showed to Ann. Watercolor, 2004.

I spent the coming weeks working on my portfolio, essays, and letters of recommendation. Later, I was overjoyed to learn that I’d been accepted into the program, and that year of intensive classes and internships went beyond what I thought it could be. Here was what I had been looking for—a way to combine my love of drawing, my interest in nature, and my training as a visual communicator. Many of my classmates came from the sciences and were developing their drawing and painting skills, and others of us were learning the science side after focusing on undergrad art and design degrees. I have a vivid memory of whispering to my classmate Justin, “what is a carapace?” when looking at a drawing of a crab during a critique. Justin kindly explained that it was the back part of the crab, without making me feel like I ought to already have known that. I was humbled by the steep learning curve but exhilarated by drawing insects under microscopes, sketching outdoors at the UCSC Arboretum, and learning to do the kind of detailed illustration that I’d wanted to do my whole life.

So what did Ann see in the hopeful graphic designer, the wannabe illustrator with her all-over-the-place portfolio? I think she saw that I’d been doing observational drawing all along. I didn’t have the words for what I was doing, but I was paying close attention to the world around me and making a visual record of it. Observational drawing underpins all my work as a science illustrator and a fine artist—a way of witnessing the world around me and calling attention to the things I want others to see too.

An early attempt at botanical watercolor from my application portfolio. Onions in watercolor, 2004.

Looking back, I’m so grateful that I didn’t get into those other programs I applied to, because they wouldn’t have brought all those elements together in the same way that science illustration did. Sure, it would have been pretty cool to say that I’d gone to the School of Visual Arts in New York or to Otis in Los Angeles, and I think I’d have had great experiences at any of the schools I’d applied to. But the science illustration program opened a door to a world I’d been seeking since I was a kid, one I’ll never tire of.

A colored pencil drawing of a snail, done on toned paper, from my application portfolio. 2005.